James Franco has made a highly successful career out of refusing to define himself. The talented actor, who has expanded his activities into writing, directing and an extremely broad take on gender and sexuality, has taken on a diverse and challenging set of roles in a relatively short space of time. From his early breakthrough performance in City by the Sea as the young son of Frances McDormand and Robert de Niro who surrenders to cocaine addiction, to Harvey Milk’s lover in Gus van Sant’s gorgeously compassionate Milk, Franco has always seemed content to adopt a position that is both central and peripheral to mainstream culture.

In Interior. Leather Bar, which showed at the Berlin Film Festival this week, Franco moves to a place that, for any other American actor or director, would be stretching the limits of both credulity and commercial viability, but for Franco comes naturally and with a certain exploratory grace.

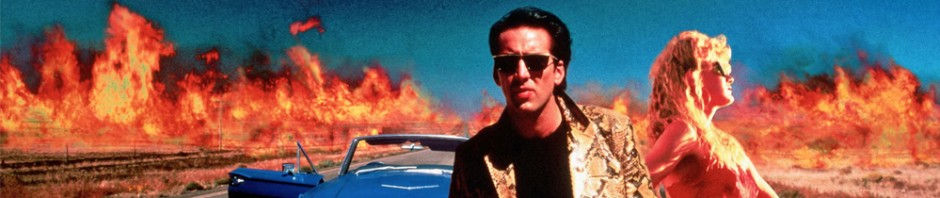

This film, which occupies a particularly unusual space between fiction and documentary, is a reconstruction of a missing segment from the 1980 Al Pacino film Cruising, which was set in the gay community of New York, and which featured Pacino going undercover as a gay man in order to solve a murder case.

At the time, the film was too much for the American censors, and in order to achieve a release, 40 minutes had to be cut from the film. Yet Cruising also incurred the wrath of the gay community, who declared the film to be homophobic and staged protests during the film’s production. Franco, together with director Travis Mathews, gathered together a band of straight and gay actors to reconstruct their imagining of the 40 minutes that were excised from the original film and which were set in a leather bar.

The result, although almost entirely removed from the normal conventions of cinema as entertainment, is a fascinating comment on the parameters of film and expression. One of Franco’s key positions – one which I’ve heard several times before from artists and filmmakers who explore the limits of cultural tolerance, and one with which I heartily agree – is the extent to which violence is shown so explicitly in movies while real depictions of sex and sexuality – straight, gay and everything in between – are constrained by a remarkably rigorous hypocrisy. Sex is a far broader expression of human reality than the kind of violence to which Hollywood has inured us, and yet it remains, even in these tolerant and increasingly accepting times, a far more controversial thing to depict with any real degree of honesty.

Franco also appeared in another film at Berlin, the equally left-field Maladies, which tells the story of an actor who has given up acting and taken on the task of writing a novel. Set in an undefined period which seems to be the early ’60s, the film features strangely modulated performances from Catherine Keener, David Strathairn and Alan Cumming, actors who, along with Franco, are all decided modern in their sensibilities. The film echoes the work of Charlie Kaufman and Michel Gondry, yet its period setting somehow neuters the post-modernity of the film, making it even stranger than the work of those cutting edge directors.

The Franco character, also named James, has recently abandoned his role in a long-running soap opera, and struggles with the nature of artistic creation and reality itself. He makes a pact with artist and sculptor Catherine (Keener, who also retains her real christian name in the film) that if one of them were to die for any reason, the other will finish their artistic work. But when James decides that he is going to start writing his novel in Braille, it all becomes a bit much for Catherine.

It’s easy to accuse both Maladies and Interior. Leather Bar of being the latest Franco vanity project. And while both films have their weaknesses, the fact that Franco is asking questions about identity that very few other actors and directors are willing to engage with makes both these films fascinating viewing.

Another film at Berlin which explores the limits of identity is the charming and filmically voluptuous documentary Bambi, which tells the story of a transexual who moves from the unhappiness of the forced conventions of his/her youth to the freedom to be who (s)he is. Consisting almost entirely of an extremely honest interview with Bambi, who is now in her seventies, as well as super-8 clips from the ’50s and ’60s, the film is both charming and extremely moving, a siren-call for truth and self-expression. In the question and answer session held after the film, Bambi was there and took questions from the audience. I asked her if she finally feels accepted in contemporary society. She answered in the affirmative, although qualified her answer with ‘not completely’. But she also said that she has always felt ‘normal’. I wish James Franco had been there.