Film: The Perks of Being a Wallflower

Film: The Perks of Being a Wallflower

Country: USA

Year of Release: 2012

Director: Stephen Chbosky

Screenwriter: Stephen Chbosky

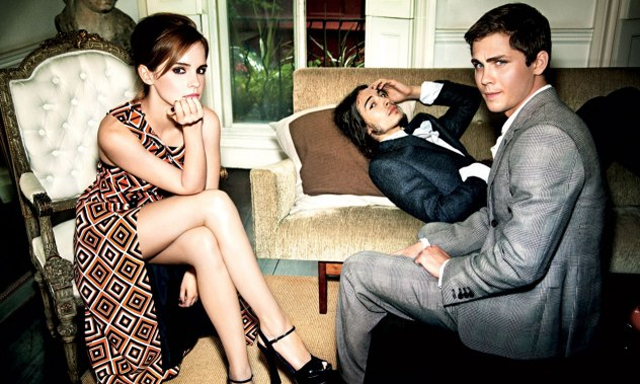

Starring: Logan Lerman, Dylan McDermott, Emma Watson, Ezra Miller, Paul Rudd

Review: Peter Machen

♥♥♥

The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a charming, if somewhat uneven, coming-of-age tale that chronicles the experiences of an introverted and disturbed young man growing up in the mid 1980s who finds his place in life among a group of misfits and outsiders.

The film begins with the first day of high-school, as experienced by the quiet and bookish Charlie (Logan Lerman). As he expects, it is a day fueled by alienation and humiliation, something Charlie has clearly grown used to. But there’s a high point to his day – during woodshop, he meets an edgy senior named Patrick (Ezra Miler) with whom he later becomes friends. Patrick, along with his half-sister Sam (Emma Watson) are the alt-dot-royalty of the high-school community, offering Charlie a buffer zone against the hordes of jocks that would otherwise swamp him physically and emotionally. With Patrick and Sam by his side, Charlie finds a new and infinitely less lonely existence, offering him – finally – the chance to live a life outside of his own haunted mind.

The resulting narrative is a familiar one, populated by the inevitable strands of alternative ’80s American youth flicks – pot brownies, acid trips, illuminated freeway drives, the heartbreak of first love and, of course, an unhealthy obsession with the British band, The Smiths. Yet, cultural markers aside, the film feels a little lost in time – tinged with the undeniable desire of contemporary culture to reveal psychological truth while, at the same time, bearing the hallmarks of a film made in the late ’90s about the early ’80s. It also contains a strong expression of our current nostalgia for an earlier and more analogue time, before cell-phones, i-pads and twitter had accelerated the culture to breaking point, specifically a time when vinyl records were still going strong and had yet to be rediscovered as a format.

It is also, like so many films about youth culture, essentially about the transcendent power of music – if the film accrues cult status, it will no doubt owe as much to its indie-powered soundtrack as to its slight and derivative storyline. And, perhaps, more than anything, viewers who were young in the period and continue to engage actively with contemporary culture will find themselves looking back to a time when music itself was a powerful expression of collective culture, something that in our fractured and hugely niched times is no longer the case.

For the first half-hour or so, the film felt strangely unsatisfying – a little too familiar in fact – as if I was watching a classic John Hughes movie, but without Hughes’ powerful and visceral sense of identification. But as the narrative progresses, and its characters slowly fill out, the film gathers it own sense of identity, and by its final moments it felt like a haunting mid-period REM song, rendered as an edgy novella in the style of Michael Chabon, its subcultural notes feeling closer to literature than alternative pop.

‘We are infinite’ is the film’s youthful – and youth-filled – coda, and to its credit, The Perks of Being a Wallflower eventually build a tangible sense of the infinite possibilities of young adulthood. I walked away from the film with the lovely transportative feeling that great cinema provides, although, paradoxically, I don’t think that it in any way amounted to a great piece of cinema. It’s not sufficiently convincing as a whole and it lacks bite and authenticity. But in its emotional swirls, cultural undercurrents and its universal search for belonging, it at least hints at greatness, even if it doesn’t begin to get there. That’s sadly, more than I can say, about most of the films on commercial circuit.

Finally, I should point out that because the film’s characters are so thoroughly immersed in the privilege of middle-classdom, it’s easy to dismiss the film as inauthentic emotionally frippery. But to do so, would be to deny the fact that growing up is never easy, no matter where you come from. This is the film’s singular emotional truth and the thing that gives it the backbone that should ideally have been far stronger.