Film: The Turin Horse

Film: The Turin Horse

Country: Hungary

Year of Release: 2010

Director: Béla Tarr

Screenwriters: Béla Tarr, László Krasznahorkai

Starring: János Derzsi, Erika Bók and Mihály Kormos

Review: Sarah Dawson

Béla Tarr began his career in film at age 10, acting in Hungarian TV adaptations of Tolstoy. And he has ended it with The Turin Horse, which he has said to be his last film, . Tarr’s first choice of career was philosophy, but he was not allowed entry to university after having criticised the Hungarian government at the age of 16, and so he went full time into making film. And the world should be grateful for this, because, in this misfortune a master was born.

His films are about ideas more than stories. They create room for thought on the part of the viewer, rather than distracting from it. Tarr is not known for what one might call ‘economical’ filmmaking. His films take as much time as they need to be told. Not only in duration, but in moments. The Turin Horse runs for 2 and a half hours, but consists of only 30-something shots in total. That means that where in an ordinary Hollywood-style production, you would see a cut approximately every 5 seconds, in The Turin Horse, the shot is broken only every five minutes. The score consists of a simple ascending/descending minor scale on an organ accompanied by detuned cello for the entire duration of the film. Given our conditioning to certain forms of media, the majority of viewers are likely to find their eyes and ears becoming bored. And indeed, as I also witnessed in a screening of his last film,The Man from London, a couple of years ago, several viewers realised within the first third of the film, that it want for them and walked out.

A deeply thoughtful film, it takes as its point of departure the story of the horse that brought German philosopher Friederich Nietzsche to psychological breakdown: he sees a cab driver whipping the stubborn beast who refuses to move, and is moved to the point of embracing the creature, sobbing into its neck. He then goes home and lies demented and mute in the care of his mother and sisters until his death ten years later. But the film is not about Nietzsche. In fact this scene occurs only in narrated voice over. The film is about the heaviness of existence. It documents the life of the cab driver and his daughter for 6 days, in their Spartan rural existence, in the midst of an unusual and ominous wind storm. Their routines do not change. And by the end, the viewer is familiar with every item they own, every mannerism and habit of the characters, every texture of their stone cottage.

What does change is a gradual slowing down of the earth around them. As though the Universe is reaching a kind of stasis. As though the kinetic force that propelled it into existence is running down. The film ends on the eve of the 7th day, and it is a kind of anti-creationist story. An apocalypse, but a banal one. Their daily meal of one boiled potato (the boiling of which Tarr makes us watch) starts out voraciously, and ends with reluctant nibbling of a raw potato unable to be cooked since the fire refused to burn, for no other reason than the laws of combustion have just given up the ghost.

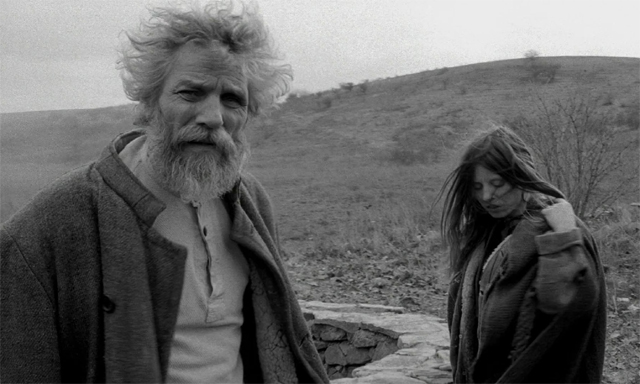

Cinematographically, The Turin Horse‘s slow, fluid black and white steadicam is close to perfection. Almost unbelievably so. As if it were a facsimile of the director’s fantasies. All the elements are of the mise-en-scene are flawless and convincing, from the constant wind across an extensive landscape, to the acting of a despondent horse, within extremely long steadicam shots that cant be tricked. The performances don’t seem like performances at all. They have a timeless, mythical quality – gaunt and weathered, as if they embody the fatigue of the drive for daily survival we all feel in the undercurrents of our existence, no matter our context.

The film is a desolate, claustrophobic and oppressive experience. It can only be watched in a cinema. Watching it at home would be a project in vain. Not least because you might just chicken out at some point. The film only does the work its supposed to do if you can’t get away. It’s endurance cinema, and not for everyone. In fact, its cinema that will be actively despised by the majority. It is difficult cinema but it is great cinema, and well deserving of the Berlin Jury Grand Prize it won this year. If you like the work of masters like Bresson, Tarkovsky and Fassbinder, you will find The Turin Horse to be a masterpiece. If you have not heard of them, you will hate it. It is a film only for those who actively seek out this kind of engagement, both philosophically and cinematically. It requires commitment and a willingness to expose oneself to the films central propositions – the destructiveness of humanity, and the quite separate destructiveness of forces of that are not human, and the need to accept that we must both claim and relinquish responsibility in a world that is destined to one day reach its end.